at18

Decentred

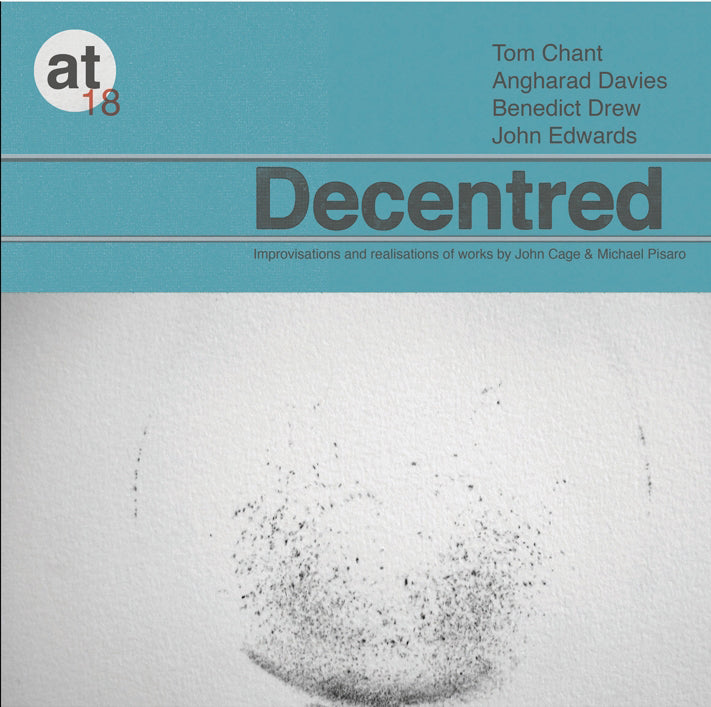

Tom Chant, Angharad Davies, Benedict Drew, John Edwards

Decentred

Featuring: Angharad Davies John Cage Michael Pisaro Tom Chant

Extract:

Decentred:

Tom Chant - saxophones & bass clarinet

Angharad Davies - violin

Benedict Drew - electronics

John Edwards - double bass

1. Michael Pisaro: Reader, listen: harmony series no.10 6:32

2. Activation (improvisation) 10:38

3. John Cage: Four 6 30:05

4. Michael Pisaro: La voix qui dit: harmony series no.8d 4:50

5. Decentring (improvisation) 13:15

6. Michael Pisaro: Flux: harmony series no.8a 3:12

Reviews

This is a gorgeous and well-recorded disc that brings improvised and composed forms together in a satisfying way. These four musicians introduce eclecticism and insight to pieces by John Cage, California-based composer Michael Pisaro and to two purely improvised structures; the best part of it all is that their respective vocabularies are so distinctive and versatile that each work is delivered with insight and spontaneity.

The two quartet improvisations certainly contain many clichés of the Euro-free improv variety, but these are just as often supplanted by the lush electronic drones more often associated with EAI. Witness the rather chatty but still sparse opening of Activation, with its pointillist dialogue gradually falling silent as jagged high-frequency sustains come to the fore. The much more restrained long tones then become an integral part of the piece, informing the quicker exchanges on their return.

This permeability of tempo and dynamic boundaries is reflected in the juxtaposition of individual timbres and motives in all of the music on offer, whether improvised or composed. The album's centerpiece, the quartet's performance of Cage's Four6, has a structure open enough to incorporate both Tom Chant's rich multiphonics and Benedict Drew's remarkably varied and emotive electronics. Premiered in the summer of 1992, it constitutes one of Cage's number pieces, which were constructed of time bracket notation. Four6's score stipulates that each player chooses twelve sounds, with fixed overtone structure and amplitude. The freedoms inherent in the score can be abused—witness Sonic Youth's rather juvenile version which relies more on repetition and novelty than on the subtlety and interplay that defines Cage's music. This quartet adheres to its choices while also embracing the silence where appropriate, but each musician finds enough diversity to ensure that the music develops over its thirty-minute duration.

The Cage and Pisaro works complement each other beautifully, both relying on the use of indeterminate structures, developing sustains and relative silence. The three Pisaro duos presented here are taken from his Harmony series (2004-2006), which was initially inspired by James Tenney's Swell Piece. Comprising 34 pieces, each using a poem as inspiration and to determine its structure, the series is a vast and stunning exploration of the intricacies of sound relations that we call harmony, for lack of a better term. As with the Cage, the scores are meant to allow freedom of choice, but the instructions are quite detailed regarding the sorts of timbres that should be used and their placement. The results can be startlingly diverse, as with the brief Flux which ends the disc. It's a stark series of quasi-pitched alternations joining Drew's electronics with wispy utterances from Edward's, the two performers even managing to match pitches despite Drew's white noise! The duo realizes the last line of the verbal score effectively, matching noise and pitch with astonishing subtlety. By contrast, Reader, Listen presents declamatory pitch complexes that sometimes give the illusion of more than two instruments at work, exactly the intricate overtonal relationships that imbue so much of Pisaro's work.

The disc is well programmed, the constant contrast between the busy improvised pieces and the slowly morphing compositions lending unity to the whole. Better still, there is a sense of discovery throughout; as with Pletnev's recordings of Beethoven piano concertos, the composed material is presented with the freshness of improvisation, and I find these solutions engaging and persuasive.”

Marc Medwin, Paris Transatlantic

“The album, is a combination of three Michael Pisaro scores taken from his Harmony Series folio, John Cage’s composition Four6 and two improvisations. It begins and ends with a Pisaro piece, with the half-hour long Cage realisation at its centre and the other tracks spaced between. The three Pisaro pieces are all scored for two musicians playing sustaining instruments. I am a big fan of Pisaro’s Harmony Series. There are thirty-four compositions in the set, each based upon a poem, or a fragment of it. The scores usually involve only part instructions for the musicians, rarely indicating particular instruments or pitches, but often describing the type of sound that should be played, with parameters set for how and when they might be used. Not all of the pieces are scored for duos, but the three pieces chosen here are for just two musicians.

The first, based on a William Bronk poem is performed by Davies and Edwards. Their realisation is a dry, sparse piece with a vaguely Malfatti-esque tone to it, slides of grey tones spaced apart by silences, sometimes coinciding with each other. Angharad has worked quite a bit in this area of composition, indeed she is one of the music’s most respected musicians, but the interesting thing to me is the involvement of John Edwards in this track, and in the album in general. He plays the piece beautifully well, as one would expect from such a skilled musician, but the piece seems so far away from what we know him as, a powerful, expressionistic bassist whose heart is rooted in improvisation. At the danger of sounding very boring through repeating myself, the fact that Edwards (and to some degree Chant) are involved with this project is testament to the current feeling of openness and cross-fertilisation prevalent in London right now. The second Pisaro piece is similar but different. Played by Davies and Chant the score asks one of the musicians to play a single pure tone for at least two of the piece’s five minutes while the other is given rough instructions on how and when they should play a certain number of pure sounds themselves. Davies takes the role of inserting the two minute sound, which she elects to play right from the outset, a quiet, hissing sound played on the violin. When she stops after a couple of minutes we are suddenly very aware of the sounds creeping into the recording from outside the church in which it was recorded. They are faint and unobtrusive, but after the continuous sound their presence is suddenly heightened, interrupted by Chant’s occasional additions to the music. This track is so very simple, like the short poem (by Beckett) that inspired it, just a few lines carefully placed in white space. The final, short (three minute) piece, based again on Beckett’s words is played by Drew and Edwards, and again the soft ambience of North London is framed by a series of short, quiet tones picked out in turn by the musicians. For me the beauty of this music is in the simplicity of it, tiny forms created with simple raw materials. The three Pisaro pieces work very well weaved around the busier Cage score and the improvisations, little interludes of calm, carefully constructed music that won’t be everyone’s cup of tea but are certainly mine.

The performance of Cage’s Four6 is maybe the highlight of the album though. The score asks the musicians (all four here) to select twelve sounds, which they then place into time brackets dictated by Cage, or rather by a randomising computer programme he used to write the piece just before his death in 1992. If the score is taken literally just about any outcome is possible. Here though the musicians work together in a gentle, yet occasionally tense and abrasive manner. The question for me here is if I would be able to guess this was an improvised work if I did not already know. Certainly it would be difficult to tell. The music has a spacious, slow feel to it because of the way the sounds are distributed amongst the thirty minute duration, but otherwise there are few giveaways. It is lovely music throughout. At times it feels very obvious that the musicians are not playing ‘together’ as they come and go at abrupt moments, but elsewhere when two or more sounds combine it feels all very natural and determined. Its a really nice piece though, a well balanced combination of sounds (presumably not discussed in advance) just enough to give the music an edge, but also to allow it all to gel together in a natural manner.

Any question about how improvised the Cage piece may have been are answered when you hear the two improvisations here though. In comparison, they sound so much more busy, wild and obviously unplanned. I have no idea how I can justify this claim, but the musicians also seem to relax when they move into the improv pieces. Maybe this is just a feeling sensed through the freeform method of playing, the restriction of the score removed, but there is almost a sense of relief audible in the first moments of each improvisation. Drew and Edwards in particular sound much more alive, boisterous and busy. Drew has often been the self-igniting firework of so many improv performances I have seen this year, and although he remains relatively restrained throughout this album it is in the improv pieces that his tense energy shines through, met well by the other musicians around him. Both of the improvisations sound alive when placed beside the compositions around them, and like Wedding Ceremony, a similar release from this year that asked a group to mix modern compositions with improvised sets the contrast between the two is marked.

It is not that one way of making music is necessarily more valid than the other, certainly not, and I enjoy all of the tracks on Decentred. The album works well for me though in highlighting how a score, however loose or simple usually results in music so very different to improvisation. The intriguing elements of this album, for me at least come through listening to the different ways the musicians respond, how those that are rarely involved in anything like this react to the constraints that composition places on the relationship they have with their colleagues, and then how they change when those restraints are removed. Decentred is a fascinating CD that probably reveals more about the musicians than the scores they are playing (something Cage and Pisaro would probably like). It is also full of beautiful, engaging music.”

Richard Pinnell, The Watchful Ear

“Working both sides of the fence between notated and improvised music is second nature to the four accomplished British musicians featured on this CD. The session’s powerful appeal lies in the sensitive maneuvering the quartet uses to personalize one long piece by John Cage (1912-1992) plus three short indeterminate scores by Michael Pisaro (b.1961). An added bonus is two mid-sized improvisations.

Buffalo, N.Y.-born guitarist Pisaro teaches composition at CalArts. A member of the Wandelweiser Composers Ensemble, his harmony series translates into sound that leaves most sonic decisions to the musicians. Similarly “Four 6”, the last of Cage’s number pieces, utilizes a computer program to distribute the 12 pre-determined sounds to four musicians playing any instrument.

As the centrepiece of Decentred, this 30-minute track takes some of its shape from pulses produced by the electronics and objects of Benedict Drew, a radio artist and soundtrack composer. Also on hand are bassist John Edwards, known for his work with saxophonist John Butcher; reedist Tom Chant, who plays in drummer Eddie Prévost’s free form trio; and violinist Angharad Davies, who plays with harpist Rhodri Davies.

Rattling objects plus Drew’s adagio signal-processed crackles and splutters set the scene for “Four 6”, with the exposition developed through intense, chromatic string plucks, wood-wrenching sul tasto lines and reed-biting slurs. With the instrumental voices closely packed, a sense of impending menace is advanced until interrupted by Chant’s wide, atonal vibrations. Pushing the abrasive string-scratching aside, his overblowing purposely almost drains the oxygen from the studio until a vibe-like ping and a whirligig shrill introduces a percussive variant from scrubbing strings. These continuous unison reverberations chug along until challenged by the saxophonist’s ear-wrenching split tones. The final variant regroups the strings’ strident textures with expanding electronic wave forms from Drew, which are patched in for split-seconds until the piece dissolves into silence. .

Chant’s bass clarinet figures prominently in the two improvisations, exposing altissimo whoops as often as chalumeau growls. On “Activation”, his tone repetitions bond spiccato string tugs, a patterning percussion beat and quivering signal processing. The title tune is more cohesive in its interaction. Characterized by radio-tuning static, sul tasto bass runs, abrasive treble-string responses and isolated reflective reed vibrations, it evolves with unexpected wide-screen-like characterizations. Spacious sweeps from both string players and mallet-like patterns from Drew plus counter-tenor-like parlando from Chant eventually synchronize despite Davies’ irregular shuffle bowing.

As for Pisaro’s indeterminate compositions, each is played by a different duo. Alternating intense interludes – which often expose affiliated nodes and partials – with protracted silences. Chant’s diffuse bottom-scrapping pitches impress the most.

Reflecting on the first-class work here, the strength of the tracks is a direct result of transforming improvisational freedom to notated scores.”

Ken Waxman , JazzWord