at246

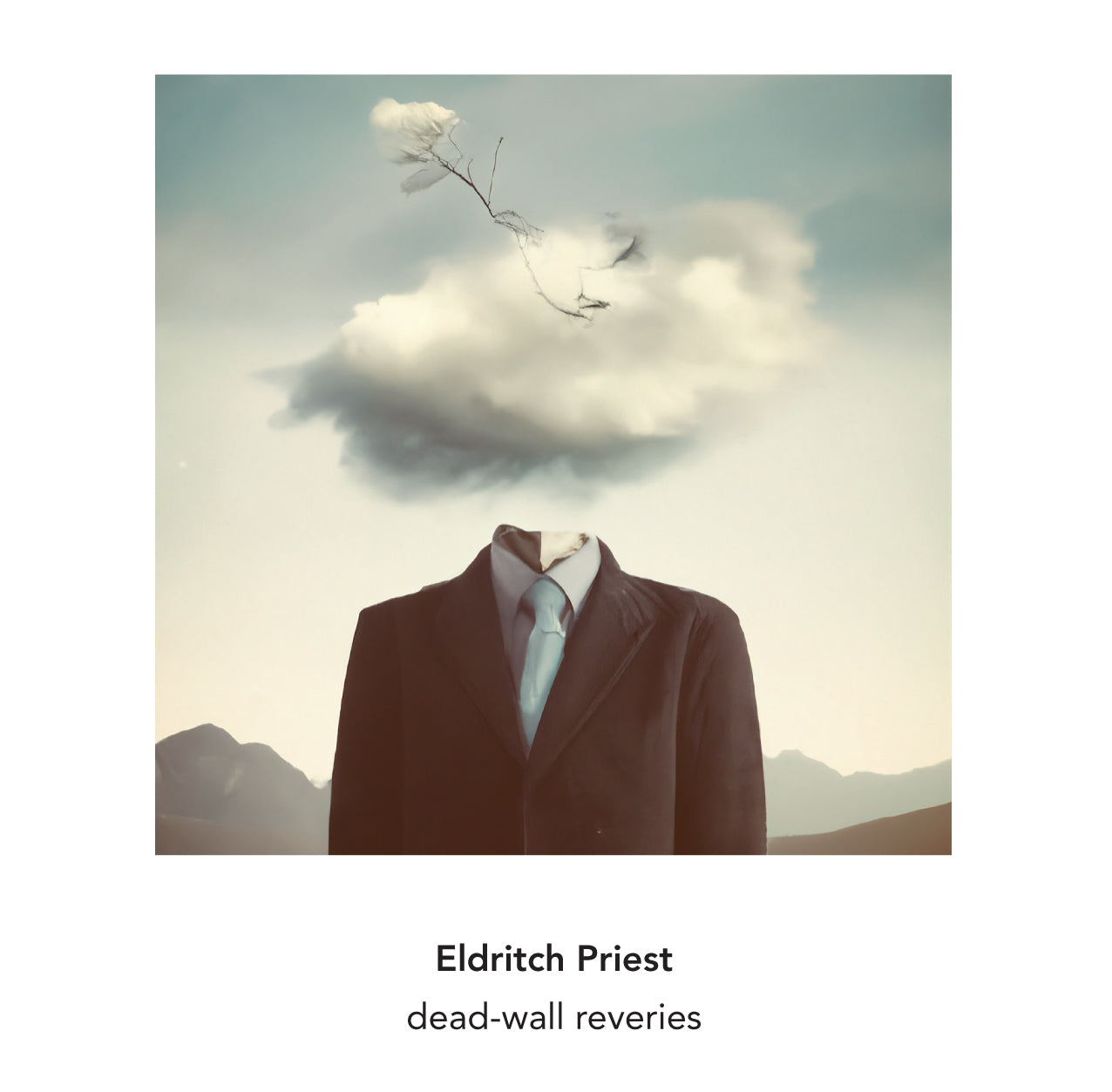

Eldritch Priest

dead-wall reveries

Eldritch Priest

Featuring: Apartment House Eldritch Priest

Couldn't load pickup availability

1 dust breeding (2023) 25:56

string quartet played by Apartment House

2 dormitive virtue (2001) 21:29

solo piano, played by Eldritch Priest

3 dead-wall reveries (2024) 27:33

clarinet, vibraphone, violin, cello & piano, played by Arraymusic

Interview with Eldritch Priest

I came across you first as a music writer rather than a composer, through your excellent & provocative book Boring Formless Nonsense. So, firstly, how did you come to experimental music, and what is the balance in your work between composing, writing, teaching & playing music?

That’s interesting that you found my writing first because, as I see it, my work as an author is actually something of a detour in what I see as a long musical career. I actually studied jazz guitar for several years in the nineties, but I very quickly moved into free jazz and experimental composition by the latter part of the decade. This move seemed rather organic to me as I was always attracted to the outer reaches of the genre. Also, I studied with a great pianist Anthony (Tony) Genge, who, as it happened had studied composition with Morton Feldman. Tony was a wonderful guide for what I see as my full-scale shift of interest towards experimental music, and like a great teacher, he introduced me to all manner of experimental composition—from Feldman (of course) to Louis Andriessen to Jo Kondo to Galina Ustvolskaya, and even Ruth Crawford Seeger. What I took most from this period of study was an appreciation for music that was radical in its methods and aesthetic commitments. I became especially interested in composers who, like my jazz heroes, had managed to cultivate a “voice,” or an aesthetic style that was singular and inimitable. Early on Feldman was a major influence, but when I moved to Toronto to study with Tony’s friend, Linda Catlin Smith, I was introduced to a group of composers, all of whom had studied in Victoria (BC) with the Czech composer Rudolf Komorous—Allison Cameron, Stephen Parkinson, and Martin Arnold. (Linda, too, had worked with Rudolf.) Years later I would move to Victoria to do graduate studies, and while I didn’t work with Rudolf (he was retired then), I did befriend him and took great inspiration from his approach to composition, an approach characterized by this uncanny marriage of the Romantic and the Surreal.

Now, to speak to the detour… As much as I loved being a musician and composer, I had throughout my university career always also studied philosophy. After completing my graduate studies, I made a decision to do doctoral studies NOT in music but in cultural theory. This turned out of be a rather severe swerve as I basically stopped writing music for five or six years. And after receiving my PhD, I spent several more years pursuing a career in academia. Although I was still playing periodically and writing the occasional work, it was only once I took a faculty position at Simon Fraser University that I feel I made a proper return to performing and composing music. Or at least, that’s my sense of things. And with regard to your question about balance… I don’t really think I’m very good at balancing my composing/performing music with my writing/teaching work. Each of these domains seems to require my complete commitment and I’ve learned that, for sanity’s sake, I tend to switch back and forth between them. I published my second book (Earworm and Event) in 2022, and since then, I’ve mostly been active composing for various ensembles and writing tunes for my jazz trio (Raymond Roussel). However, I’ve another book that I want to write, so I suspect I’ll be shifting gears again. But that said, I’ve gathered a bit of momentum these past few years, so I’m hoping to find a way to accommodate both my musical and academic interests.

That’s interesting. For me listening to music excites very different parts of my brain from whatever academic, cultural or political interests I have at the time. So I completely get that it’s hard to pursue composition/playing on the one hand, and writing theoretical texts at the same time, even if those texts are about music. But do you also feel that – however indirectly – the theoretical thoughts you have do affect the music you compose?

I’ve been asked this before and, yes, I do feel that there’s a way in which my theoretical work informs my artistic practice. However, as you suggest, I think this happens in a very indirect way. It’s actually easier for me to see it the other way around—the way my artistic practice affects my theoretical writing. What I see as the kind of logical leaps or rational hiatuses that inform art making (or at least my art making) often find their way into my scholarship in the form of arguments that take paradox and nonsense as valid modes of reasoning. I also think my creative work informs the way I see “style” as a legitimate register of theoretical thinking. How it works conversely is a little more mysterious to me. I’ve been told that my compositions are more “sensuous” than “cerebral.” But I’m not certain I buy that dichotomy, if only because the latter is no less a felt affair than the former is. I also think that music is itself a mode of thinking, one whose symbolic content is meaningfully indistinct from what is symbolized. In this respect, the feelingfulness one senses (perceives?) in/through music is confused—delightfully so!—with the affective experience that it denotes. (Maybe this account is too cerebral….) Perhaps there’s also a way in which my tendency to play fast and loose with concepts (in my theoretical work) in order to draw out their less obvious resonances finds its way into my compositions as a kind of aesthetic/expressive dalliance. The works on this album, I think, exemplify what I mean by this, in the sense that in them I flirt relentlessly with a musical idea in order to elicit (or encourage) a manner of listening that blurs the distinction between a trivial regard and focused attention.

When we began planning this disc, 'dust breeding' was the starting point. In fact, you sent me two different versions of the piece. Could you explain its instrumentation & history, and how open is the score?

Yes, that’s right, dust breeding was the beginning of this project. For me, dust breeding is a work that takes the conventions of chamber music for a quiet ride across a fragile surface of sound, where pitch, noise, intention, and accident pass playfully through each other’s territory. In this piece, the performers are asked to play sounds that are unstable, yet sonorously and harmonically rich in their delicacy. The image I have in mind is of dust (noise) swirling over and gradually settling on the structure of the string quartet.

My aim in writing this work, wasn’t to deconstruct or reinvent the string quartet, but rather to experiment with and perhaps even exaggerate the expressive potential of sounds and textures that I would characterize as “glass-like”— translucent and frangible. At the same time, I wanted these sounds to have a certain opacity. Hence the “dust-like” quality of the string and bow noise as well as the odd “wrong” (but, oh so right!) note, which work together to produce subtle sonic artefacts. As I hear it, this means the music is at times begrimed in a way that contrasts with the vitreous touches of the melodic and harmonic content.

I wrote dust breeding specifically for Apartment House after recording some cello solos with Anton Lukoszevieze. There’s a section in one of the solos that features an extended passage of harmonic-like sounds/noises activated by lightly touching the strings where there are not necessarily any nodes. This technique produces an effect that is both transparent and obscure, and I wanted to probe the potential of this effect in a context where things could be a little more “shambolic.” That is, where these sounds appear in the cello solo in a very direct and deliberate way, in the quartet they seem as if accidental and random. But you’ll note that I wrote “seem,” meaning that the ramshackle quality dissimulates what is actually a very specifically notated performance. So, the score is not, in fact, very open at all. Yet, at the same time, the performers never use a traditional bowing technique. They are either making those harmonic-esque sounds, playing col lengno tratto, or col legno battuto, such that every event has some layer of random noise, of “dust,” added to the sound. In other words, I like to think of dust breeding as chamber music with dirt in its eye.

That’s all really interesting. What about the piano solo, dormitive virtue? You recorded this yourself in your apartment, and in a way the music sounds more like a semi-private, reflective improvisation than the other pieces on the disc. Is that accurate? Or was the piece fully written out before you played it?

Like all the works on this album, dormitive virtue is a fully composed piece. That it sounds improvised is a wonderful compliment! I’ve been trying for years to cultivate a compositional sensibility that gives the impression of being somewhat “offhanded.” This is the oldest work on the album and one I think shows just how much under the spell of Feldman I was. I’m not suggesting that it sounds like Feldman, so much as its “reflective” and drifting character produces that kind of paradoxical situation, where music can be both blithe and thoughtful. I think (I hope) my more recent work still seeks this kind ambiguity, but does so through a very different gestural language. To me, dead-wall reveries, the title track, aims for a similar type of enigmatical repair, but through a much more lyrical and, dare I say, expressive grammar. Without insinuating anything Romantic or sentimental, the work tries to muster an aloof yet friendly kind of melodic play that, like daydreaming, strays impassively from one moment to another. In this regard, there’s a continuity of spirit between my older and newer work. But there’s also clearly a break in the manner of articulation, one, I suspect, that reflects my interest in improvisation and a long-held love for melodies that go wonderfully nowhere (and everywhere). For instance, unlike dormitive virtue, dead-wall reveries is loaded with notes and an abundance of lyrical bits, but, ironically, none of them matter! Or, perhaps, they all matter equally in their seeming shiftlessness and resistance to forming a hierarchy of events or actions. Although I expect it’s not for everyone, I find this kind of situation in music and art to be extremely appealing.

Yes, dead-wall reveries is a very unusual piece, and strikingly diverse stylistically. It shifts restlessly between busily melodic passages and slower, more reflective sequences. As you say, there is no evident structure which the listener can grasp, so it’s a disorienting, but strangely engaging, journey. It’s the most recent piece on the album, so is that the direction that your music is heading in general, or is it a one-off?

As you mentioned, dead-wall reveries is a bit disorienting, but there’s something about how it moves back and forth between styles that I find seductive. I think the casual toing and froing of it all maybe sets up an uneven refrain that modulates attention in weird ways throughout the work. It makes me think of Carl Stalling’s work, but much slower…and less Looney Tunes. This is certainly something that I’ve started exploring more deliberately in my work. For a long time, I was fascinated with trying to exhaust a single musical idea. Much like the writer George Perec once attempted with a space in Paris, I would tarry with the details of a particular gesture or textural figure and work to unpack its latent features. But these days I’m a little more interested in seeing how things can shift without being particularly dramatic or precious about it, like the way our thoughts can wander from topic to topic without drawing attention to the fact. Yet occasionally this back-and-forth refrain seems to work a little like Sergei Eisenstein’s approach to montage, an editing technique that sees the sequencing of disparate images (or styles) as producing another order of meaning or import. This isn’t to say that I think dead-wall reveries is cinematic in its logic—or Marxist in its politics. I think it’s much more promiscuous than that as it flirts with more than marries any kind of dialectically informed progression of ideas. Maybe what I’m after with this work is something gently lurid, something oxymoronic that goes and stays where it always will have been.