at116

Olivia Block

Olivia Block

Featuring: Olivia Block

Interview with Olivia Block

How did you develop the work on your CD? Was it through-composed or improvised, or was it a combination of the two? And is the method you used for this piece fairly typical of your compositional practice?

This suite was created over a span of several years. I developed techniques inside piano through rehearsals and performances, sketched the basic ideas out--the motives, physical materials, etc., leaving a lot of room for improvisation between the composed bits. I think of the suite as somewhat modular. I can switch sections around while key features, like patterns on the keys in each section, are composed.

There are certain aspects that are unpredictable by nature. For instance, the resonant notes inside the piano, amplified through the contact mics and mini speaker, lead the note choices I play in the keyed patterns.

So in terms of live performance, each piano and the materials I place inside the piano become key factors. The score sets these processes in motion, but leaves room for my spontaneous reactions to the natural acoustic phenomena within certain boundaries.

Why did you choose to present the piece without a title?

In contrast to most of my recordings, these pieces are relatively unedited. I recorded them live at Electrical Audio studio here in Chicago, only adding a slight amount of post-production detail. Most of the extra production intervention happens during the performance with a micro-cassette recorder, played back inside the piano.

So the lack of title reflects the fact that the suite is more direct, and in a sense, bare, of layers or extra elements. It’s basically just me playing piano and objects. This is the first time I have worked with a co-producer, Adam Sonderberg. Adam initially suggested leaving the title blank and I liked the idea and went with it.

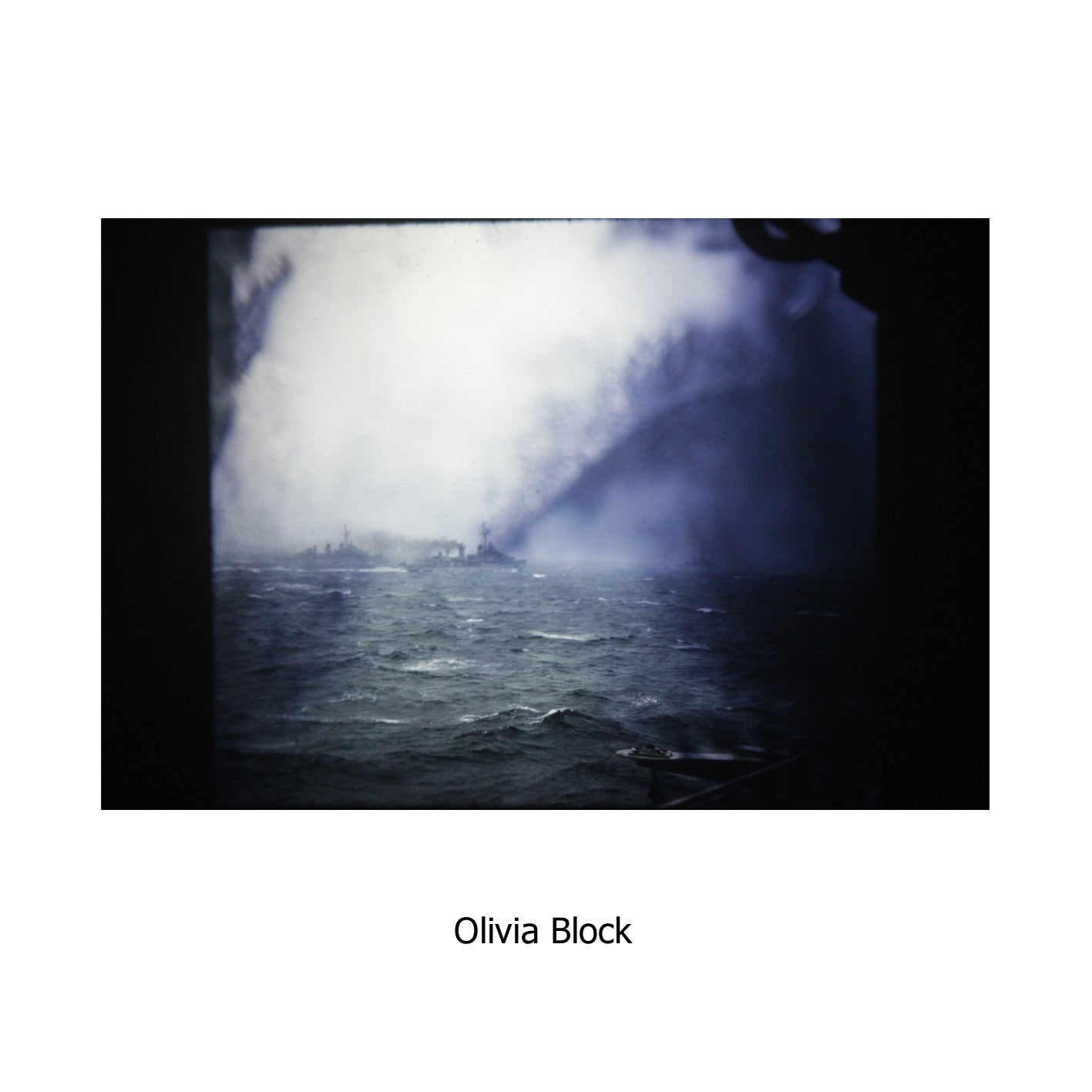

The image on the CD cover is striking. What is it, and does it have a connection to the music?

The image is a projection on a wall of a custom slide I created from two layered 35mm “found” slides from my slide collection. To me, the image is related to the suite in terms of mood and impression. The feel of the blue and white, and the images of the water match the timbral qualities and pacing of the suite.

What is your musical background and training? And how did you come to experimental music?

I have a degree in biological anthropology, but I also attended a music conservatory and art school for sound. I think of myself as auto-didact, though.

My initial training was when I was really young in Austin, Texas, playing in bands and working as an assistant in recording studios.

I started listening to experimental collage and noise music when I was still in bands. I also discovered the music of Scelsi, Annea Lockwood, Phil Niblock, Ligeti, Jim O’Rourke, Harry Bertoia and the horn and cymbal music from Tibetan Buddhist monks.

I got a four-track recorder and started making solo tape collages. The band I was in played the collages in between songs. Then I wanted to quit the band and focus solely on the studio pieces. I bought a cornet at pawnshop and then only wanted to play cornet instead of guitar.

At around that time in Texas I met Seth Nehil and John Grzinich. We started a trio, Alial Straa, performing and improvising in unconventional, acoustically rich locations. We performed in a drainage tunnel and used the rocks and leaves there as instruments. We made field recordings with a portable DAT recorder and used them in shows with amplified objects.

As I progressed in my solo practice, I wanted to work with ensembles of musicians, adding a different live component to my performances. When I moved to Chicago in the late nineties, I became connected with Jim O’Rourke and the improvisers in his orbit like Jeb Bishop and Kyle Bruckmann.

At first I mostly worked with improvisers, but over time, I composed scores for the musicians to play, which I could then record and add to my studio pieces later. After that, my ideas for scores became increasingly complex, and the combinations with studio-based sounds and musicians became more elaborate. I decided to gain a “formal education” in music composition.

I became fixated on making orchestral music. I thought about it and talked about it constantly. I wanted to study music formally because I needed to learn proper notational techniques for that medium. When I was studying at the conservatory I requested to be paired with teachers who used conventional notation. I wanted to know where to put the slurs and indentations properly.

I could then create pieces for the orchestral reading sessions and try out ideas. I started thinking about how I wished orchestral music allowed for more improvisation in rehearsals, and thought about the social structures of music-making which contributed to my interest in anthropology.

I had several solo recordings released before attending music school. I couldn’t finish at the conservatory because my touring schedule got in the way. I was older than the students there. I finished a degree in anthropology at Northwestern instead, attending school between my music-related trips.

Your work varies from purely electronic works, through live improvisation to fully scored orchestral pieces. Are you happy working in all the genres your work spans, or do some of them feel closer to you?

Sometimes I wish I had a narrow focus in my practice. I think it would be easier to explain myself to people! But I keep expanding into different aspects of sound and music and other media. To me, these different branches all express my own sensibility and interests, so they related in my mind.

I feel most comfortable in my studio working with recordings and electronic processing techniques. I love sitting down with headphones or in front of speakers and listening to ideas, changing them, listening, and so on.

I am more adept at listening than at reading notation, so the least comfortable process for me is notating pieces, particularly if I am using conventional techniques (I often combine conventional and “experimental” notation techniques).

It takes me a long time to score something that I could simply tell a musician to do in a few minutes. Then, when I listen to the notated idea performed, it doesn’t sound right and I need to go back and rethink the scoring techniques. The process feels inefficient and complicated, but necessary, of course.

Often I finish notating a score after I record the piece and all of the trial and error with musicians or myself is worked out. I listen to rehearsal recordings or concert recordings and notate the piece in retrospect.

Now I am using old science experiments and other found texts as scores for performed pieces, which is a little more comfortable. This part of my practice is the least related to my studio work, in that the score leads the entire the process, whereas I usually hear a sound from my studio recordings or imagine sounds, then want to notate afterwards. That is the reverse of the ‘norm’ I guess.

From across the ocean, Chicago seems to be quite a vibrant centre for experimental music of various kinds. How do you see it, and do you feel part of a local ‘scene’?

The Chicago experimental music scene is thriving now. We are in a moment here where there are competing experimental or new music performance events almost every night of the week at various venues in town. It’s a great problem to have. I travel a lot and when I am home I stay in a lot and work in the evenings, but I still feel very connected and supported. There are many organizers, musicians and composers I love here.

Reviews

“Chicago-based musician Olivia Block has been notably subtle and successful in blending environmental recordings with instrumental voicings and electronic sounds. Her acute compositional ear responds to changes in the timbre of rustling leaves no less than to the percussive drama of a hailstorm. For some years she has brought that discernment and sensitivity to her exploration of the piano as an acoustic ecosystem, introducing various objects into its interior and using amplification to modify and expand its sounding range. On this untitled suite in three movements, essentially a live performance with minimal subsequent intervention, notes fall from the piano’s keyboard like water droplets from a ledge giving rise to sonic micro-organisms that take on a life of their own. Sparsely patterned tones spawn textures and shadings that open onto a far more mysterious musical biome. Strange beauty compounded by an enigmatically resonant cover image that Block has created too.” Julian Cowley, The Wire

“The CD cover for Olivia Block’s new solo release on Another Timbre is spare, even for the standards set by that label. The CD has no title, the three pieces are simply titled I, II, and III, the only annotations is that Block is credited with “piano and organ” and it is noted that the recording was made during a single session in Chicago. The structure of the CD has a certain palindromic simplicity as well, with the first and third pieces running a bit over 13 1/2 minutes and the central piece running exactly 8 1/2 minutes. Take a listen and the music strikingly aligns with the graphic austerity of the cover. Each piece delves deeply in to a particular timbral range, and each explores the nuances of the piano as both sound source and resonator. At the core of each is a sense of sonic investigation, setting up the piano with preparations and treatments that push the instrument and the way it interacts with the acoustics of the recording studio.

The first piece starts with crystalline, percussively struck pairs of notes at the top of the keyboard, with space left to allow the decay of the tones to hang. Gradually, Block moves the motifs down to the middle register of the piano, introducing rich chords and the jangling sound of prepared strings while calling up ghost tones and shadowy textures to fill in at the edges. Pacing here is paramount, as she parses out each figure and chord progression, accentuating sharp attack and maximizing the resulting overtones and resonances. Toward the final section of the piece, layers begin to build with a gauzy transparency, bringing to mind the way that light radiates through stained glass, filling a room with the resultant chromatic tints.

The second piece makes far more use of preparations with quietly ticking motors, percussive flurries, and struck strings accruing into a shimmer of detail. The pace is much more rapid as well, and the gestures of Block’s playing are more apparent, choreographed against the low rumble of bass chords. The patter and hum of incidental sounds also emerge, including the low hum of organ and the pings and twangs of the strings projected back in to the instrument. In the final section of the piece, volume and density peak, opening up to squeaks and creaks against the low buzz of the organ. Here traces of mechanical sounds accentuate the duality of the piano as string instrument and percussive mechanism.

The final piece expands the sonic spectrum further, accentuating the lower registers and utilizing abrasions and filtering of the natural string resonances. The dark colorations of organ are also more pronounced. The dusky registers have a decisive impact on the internal feedback loops of mic’d and amplified aural vestiges of the elemental sounds of the piano, providing granular shadings that fill out the sound palette. Like the first piece, the pace is stately and methodical, with each chord placed with mindful purpose within the overarching flow. In the last third, the sharp, glassy notes of the opening piece are gradually incorporated, bring the suite full circle. Block often works with multi-channel installations and one can hear how that sensibility comes through in the intimate format of this recording, using the placement of treatments and amplification of the piano with an analogous approach. Adam Sonderberg’s meticulous production is another element worth noting as he captures the playing with brilliant spatial clarity."

Michael Rosenstein, Point of Departure