at96

Bryn Harrison

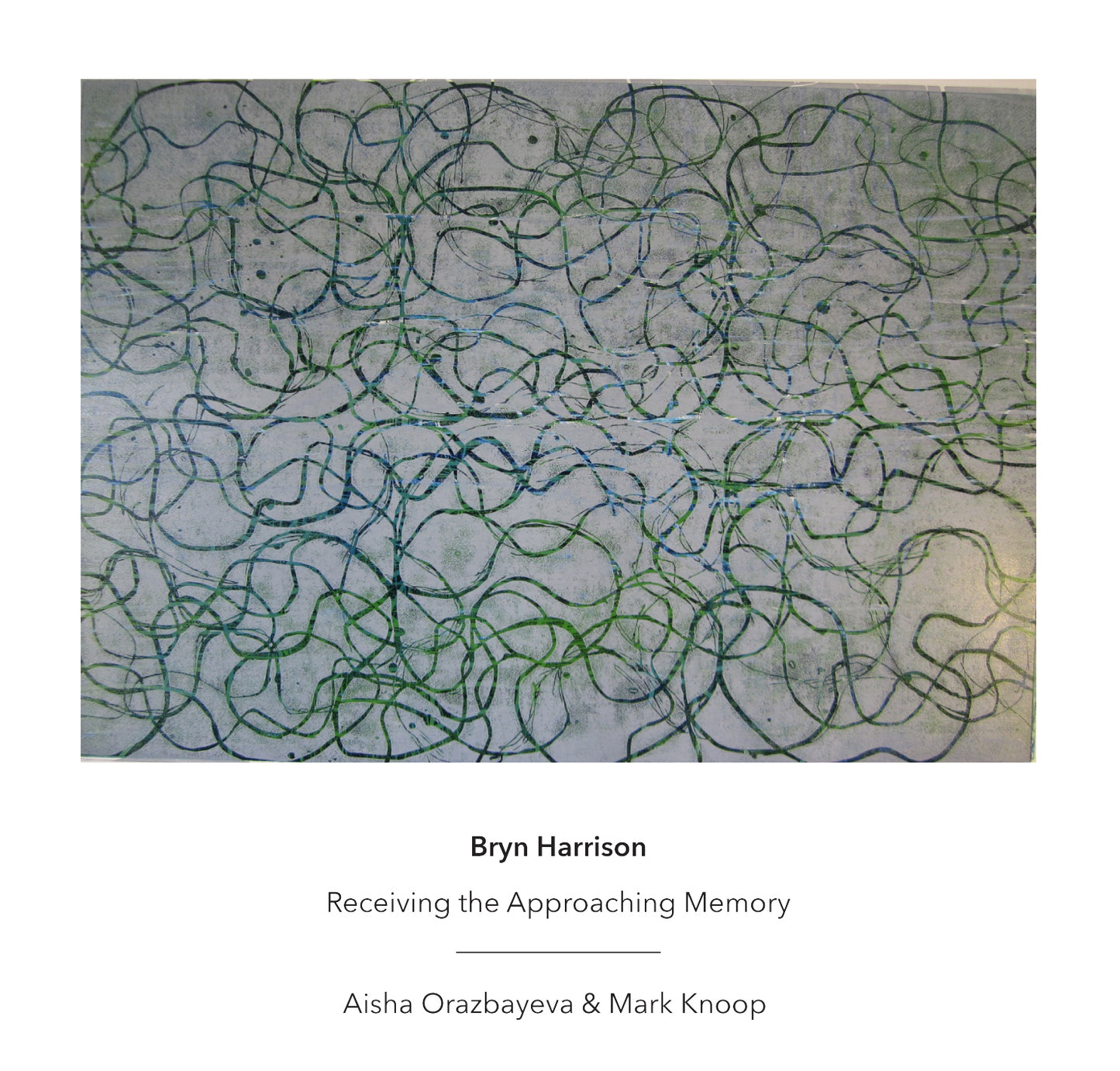

Receiving the Approaching Memory

Bryn Harrison

Featuring: Aisha Orazbayeva Bryn Harrison Mark Knoop

Couldn't load pickup availability

Aisha Orazbayeva (violin) & Mark Knoop (piano)

Recorded in Bremen, July 2015

Total time: 38:50

Interview with Aisha Orazbayeva & Mark Knoop

What drew you both to Bryn Harrison's music, and what would you say are its strengths?

MK: I came to Bryn's music through Matthew Shlomowitz and Joanna Bailie, the directors of Plus Minus Ensemble, who asked Bryn to write a piece for the ensemble's very first concert, in 2003. That work, 'Rise', immediately attracted me by the way it created an immensely detailed surface texture that still allowed for great clarity in the form and direction of the piece. Since then, Bryn wrote us another, much longer work, 'Repetitions in Extended Time', which takes both these aspects even further: extremely high levels of local detail serving an almost monolithic global form.

AO: My first encounter with Bryn’s music was ‘Leaf Falls on Loneliness’ which I performed with the Ossian ensemble in 2010. The piece made an impression and stayed with me for a long time. When Mark told me that there’s a long piano and violin piece I jumped at the opportunity to perform it. In his music I feel like Bryn introduces another world, but one that we cannot see at first, and the repetitions are the way to get closer to it so that every time the music repeats the world comes closer and closer to us, revealing its colours, shapes and architecture.

There is obviously a long history of compositions for violin and piano, and it’s probably either impossible or foolish for contemporary composers to ignore or forget that tradition. Do you think that in a way that is part of what we are ‘receiving’ when we listen to Bryn’s ‘Receiving the Approaching Memory’? How do you feel the work relates to or diverges from the tradition of classical violin sonatas?

AO: I don’t really see this as a ‘violin and piano’ piece in the traditional sense, I feel like it’s more about the sound, texture and form of the piece rather than the instruments. It’s highly virtuosic at the same time, but that aspect is not at the forefront, the difficulties are hidden from the listener and the performers are somehow hidden too.

MK: I had not considered that interpretation of the title, although it’s an interesting thought. Whilst Bryn’s music is of course influenced by the canon (as is all music), I don’t see him as a composer who is primarily engaged with reinterpreting that tradition. Having said that, a parallel could be made between the tonal structure that underpins sonata form and the way tonality develops through ‘Receiving the Approaching Memory’. The piece is in five sections: in the first, both instruments’ pitches are drawn from a complete chromatic pitchset. In subsequent sections, different pitches are removed from each instruments’ part so we have fewer common pitches (just C and F in the final section). Whilst I don’t think this is consciously perceived as “tonal” development by the listener, it certainly creates a subconscious sense of progress in what is otherwise essentially static music.

You recorded the piece in the famous Sendesaal at Bremen radio. How did that come about, and did it feel like a special venue?

MK: I’ve been aware of the hall for a while, and recorded and performed there several times in the last few years. It was built in the fifties and features a mid-size hall with an exceptionally clean acoustic, suspended on springs and isolated from the exterior of the building. This acoustic was ideal for Bryn’s music, giving the necessary clarity for the detail of the piece without becoming clinical or dry.

AO: I’d never performed in the hall before, but it was a joy to play and record there, and felt like a very special venue.

Both of you have moved to the UK from elsewhere, and I wondered how you both saw the experimental music scene here? Are there aspects that you feel are particular to this country, and are there any features which you regard as particular strengths or weaknesses?

AO: I left Kazakhstan when I was a teenager and back then my only violin preoccupations were to do with good intonation and drawing a straight bow. I became aware that there is an experimental music scene at all, not just in London, after I realised the formal violin training that I had since I was four was often not about the music, but a certain prescribed way of performing a certain prescribed repertoire. When I began studying with Clio Gould my focus gradually started to shift from achieving a perfect result to the process of discovering new ways of making music and a more personal relationship with the instrument. This change in the way I thought about music led me to discover the experimental scene in the UK, so far it’s the only one I’ve experienced.

Bryn Harrison

Reviews

“If you don’t know the deft and gossamer music of Bryn Harrison, this album would be a beautiful place to start. The Bolton-born 40-something fits broadly within a British contemporary music bent for clever, subtle minimalism – his own heroes are Feldman, Messiaen, Skempton. There is, though, something especially economical and fantastical about Harrison’s sound; something in the way he repeats and interlocks fine-grained, shimmering material and keeps us spinning in a magical place between stasis, flux and momentum. He wrote Receiving the Approaching Memory for violinist Aisha Orazbayeva and pianist Mark Knoop in 2011 and they do it marvellous justice: violin lines flit about, birdlike, against a glittering piano backdrop, both instruments sounding as quiet and urgent as a whisper made on an inhalation. Orazbayeva is a taut and boisterous player who doesn’t let a single note rest: this music might be repetitive, but every moment is alert, agile and ready to take flight.”

Kate Molleson, The Guardian

“I won't forget the new "Receiving the Approaching Memory" for a long time. It's a wonderful piano/violin duo, a long dream, near of speech, constructed on melodic repetitions and a very creative use of violin. Highly recommended.”

Julien Heraud, Improv-Sphere

“It is one thing to receive something, and quite another to know just what to do with it. That is the essential gift of Receiving The Approaching Memory, a piece by English composer Bryn Harrison. He has selected a delivery system that can easily stymie recognition and understanding; how easy is it to hear a pianist and violinist playing music that is recognizably from the classical tradition and simply perceive “piano” and “violin” without hearing a damned thing either instrument plays?

Harrison builds upon some recognizable 20th century musical methods associated with minimalism — extended duration, apparent simplicity, unapologetic repetition — and made something that doesn’t feel like a rehash, but doesn’t seem to make a point of that either. The piece is broken into five parts, each of which sounds so similar to the other that a casual listener might think they were hearing the same thing over and over again. They’re not. In an interview published on the label website, pianist Mark Knoop explains that over the course of the performance Harrison subtracts pitches from each player’s parts so that they have less and less tonality in common. This creates a contradictory experience wherein the music sounds like it remains the same but feels like it is not, which invites you to listen, and listen some more in order to decode its paradoxical effect.

It’s as though someone took a piece of Morton Feldman’s music, distilled it into liquid form, and then dispensed it five times with an atomizer bulb. Each cloud seems the same, but each is unique. Knoop and violinist Aisha Orazbayeva do not play mere droplets of sound, though. They inhabit Harrison’s drizzling keyboard figures and dancing bow strokes as well as the acoustics of the space in which it was performed in order to render music that glints with brightness and detail.

So what is this thing that Harrison has delivered? An experience instigated by music, but one that challenges the listener to consider what they hear and what they remember and how the two relate. He has used a familiar format to instigate a new awareness of the act of listening.” Bill Meyer, Dusted