Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at206 Eden Lonsdale ‘Clear and Hazy Moons’

Apartment House & Rothko Collective

1 Oasis (2022) Kerry Yong, keyboard Mira Benjamin, violin Heather Roche, clarinet

Anton Lukoszevieze, cello Sam Cave, guitar Simon Limbrick, percussion

2 Billowing (2022) Mira Benjamin, violin Bridget Carey, viola Heather Roche, clarinet

Anton Lukoszevieze, cello James Opstad, double bass, David Zucchi, saxophone

Rebecca Toal, trumpet Nancy Ruffer, flutes

3 Clear and Hazy Moons (2022) Leon Human & Anna Brown, violins Dominic Stokes, viola

Sandy Scott-Brown, cello Lucy Walsh, alto flute Izzy Hopkins, bass clarinet

Toril Azzalini-Machecler & Isaac Harari, percussion Sebastian Flore, piano

4 Anatomy of Joy (2022) Mira Benjamin, violin Bridget Carey, viola Heather Roche, clarinet

Anton Lukoszevieze, cello James Opstad, double bass, David Zucchi, saxophone

Rebecca Toal, trumpet Nancy Ruffer, flutes

Youtube extract 1 (Billowing) Youtube extract 2 (Clear and Hazy Moons)

CD copies sod out but downloads still available here

Interview with Eden Lonsdale

I guess a lot of people won't have heard about you, so can you tell us about your background and how you came to experimental music?

I started making music when I was 9 with my cousin, who is the same age as me. For about three years we met up every weekend and spent hours and hours making beats, writing lyrics and recording rap tracks - we were incredibly devoted to it…

At some point around age 12 there was a sudden flip. Pretty much from one day to the next I started enjoying playing the cello, which I had also been taking lessons in since I was 9. I stopped throwing tantrums every time I had to do my 15 minutes of daily practice and reshifted my musical focus. From then on I spent my weekends listening to Bach’s Cello Suites or Inventions & Sinfonias on repeat, whilst following along in the score. To this day I am abnormally fascinated by the Inventions, I think…

Soon after that I started composing a lot. Préludes and fugues in the style of Bach, although it was entirely by intuition and not until years after that I received any kind of formal training in theory. I almost never finished anything because I simply lacked the ability and what I did finish was not good.

From there on the rest is history: with my very weak portfolio, I somehow got a place to study at Guildhall and as soon as I became immersed in the environment there, it became clear very quickly where my music wanted to go. Being surrounded by composers such as James Weeks, Paul Newland, Laurence Crane and Cassandra Miller, and through them finding my way into the universe of Another Timbre, Wandelweiser, Plainsound and so on. These were my stepping stones into this kind of world, although I have never thought of myself as an experimental composer. In my mind I am still writing little baroque canons.

Guildhall seems to have become an excellent centre for composition, with very good teachers, and a lot of very interesting young composers emerging. Are you still linked to Guildhall, or is that now in the past?

Of course I am still in touch with people there, but considering that I graduated just over a year ago, it feels surprisingly distant. I’m very much not an academic, so honestly I feel much happier outside of institutions where I can just get on with writing my pieces. I enjoyed the environment and the practical aspects of studying, but I feel much more like myself in my current situation where I can focus on writing for its own sake.

One thing that I love about composing is taking it piece by piece, seeing what works in the one and picking up where you left off in the next. This way the music - your body of work - can find its way into a trajectory of its own. For instance, my pieces have started to become longer since I left university, a development that may not have been possible within those confines. It feels like the music can grow in whatever direction it needs to grow and I am just along for the ride, rather than trying to squish it into some kind of corset.

Do you compose with any sort of system, or is it purely intuitive?

I have long been suspicious of this distinction that people seem to find between ’intuitive‘ and ’systematic‘ composition. To me they are not opposites but rather intrinsically connected.

What I personally never do is to sit down at the piano, writing one note, then another and another according to what I fancy in the moment but to be honest I believe it’s an illusion to think that anyone works this way. I also don’t know any composers who will just churn out a calculated process without any prior idea of what it might sound like and stick with the results no matter what - there is normally some give and take on both fronts.

For instance, somebody writing at the piano might have forgotten that the melody they invented ’freely‘ is in fact moving within the confines of an extremely limiting and utterly abstract system called equal temperament. At the same time, I use what I think of as systems extensively in my compositions, but their use has actually become entirely intuitive.

I am fascinated by systems and processes because they are responsible in most cases for what intrigues me about music. Sound has the ability to turn your experience of time almost into an experience of physical space, that you can enter and investigate freely, like a parallel universe that obeys its own laws of nature. Everything in our world can be said to appear the way it does because of a set of intangible fundamental laws and equally, soundworlds appear the way they do because of the systems that were used to create them. Systems provide these laws and processes are ways of moving through these systems based on the laws they establish, just as humans developed walking upright on two feet as a means of moving in response to the gravity of the earth.

Many people somehow think of classical tonal composition as the epitome of ’intuitive‘ writing, but in reality tonality is one of the strictest systems ever used in composition. Processes - such as sequences - are very common in tonal music as a means of moving through the space established by the system. My point is that whatever one thinks of as being either ’intuitive‘ or ‚systematic‘ is never only that and always holds the other within.

Tell us about 'Clear and Hazy Moons' and the Rothko Collective. Was the recording taken from a live performance, and what was the context?

Rothko Collective are a very young group of players that I met and became friends with towards the end of my studies. Dom Stokes, the violist who runs the group, quickly made a name for himself amongst the composers for being really invested in new music - he‘d always give a very committed and musical performance.

In 2021 he asked me to write a piece for his newly founded group Rothko Collective, which went really well, so we did it again the following year. ’Clear and Hazy Moons‘ was written for a live performance at the church of St.Giles Cripplegate in London in April ’22, and the recording was made on my handheld zoom during the dress rehearsal.

Finally, what about the three pieces that Apartment House play on the CD: ‘Oasis’, ‘Billowing’ and ‘Anatomy of Joy’? How did they come about?

Of those three pieces ‘Oasis’ is the oldest and was actually the last piece I wrote while I was still a student, for a project with plusminus ensemble. Shortly after I finished it, Anton Lukoszevieze got in touch and said that Apartment House wanted to play it. That was the first time I was in touch with Apartment House - a group I whose work I had been admiring from afar for a long time - so it was very exciting.

The other two pieces are both from 2022, ‘Billowing’ being the first piece I wrote that year. It was made for a friend’s group called the listening project and was premiered at a pub in Whitechapel, a space it was probably not best suited to… I had to write the piece in a short amount of time, so I decided to make it out of a single line, which I subjected only to very basic techniques: augmentation, diminution, transposition, chopping up and a few more. The melody I used for this was something I wrote down when I was at Huddersfield CMF in 2019 - a sketch for an eventually abandoned saxophone quartet. I am now quite aware that it is not dissimilar to a certain melody by Stravinsky…

Finally ‘Anatomy of Joy’ was written in September 2022 specifically for this recording and doesn’t so far have a life outside of this disc. It is quite closely related to ‘Billowing’ in that they share the same instrumentation and I used that opportunity to deepen ideas that had emerged during my first engagement with this line-up. In essence the techniques I used are all the same as in ‘Billowing’, again using a single melody to structure everything, except that the melody here is longer and more complex and is continuously chopped up and rearranged from the very start.

One thing I find intriguing about the selection of pieces on this CD is that they were all written roughly within a year of one another, but span a period of time in which my music changed quite significantly. ‘Oasis’ came out of a stretch where my music was focused mainly on vertical parameters like harmony, timbre and resonance and was searching for a listening experience that is totally anchored in the present moment.

‘Billowing’ was the first step in a new direction that tried to reengage fully with the passing of time by integrating prominent melodic elements.

‘Clear and Hazy Moons’ is curious because it lies right between these two and has different sections that fall onto either side of this development.

What I am currently after are pieces that can be experienced in multiple simultaneous ways or have dimensions that allow for different readings and interpretations. For instance, pieces that are essentially static but always in a state of flow, or pieces that are essentially flowing and always in a state of stagnation. Being the youngest piece on this record, ‘Anatomy of Joy’ is the most representative of this and in many ways to the most successful piece at achieving what it was intended to be.

Detail from ‘November’ by Gerhard Richter

‘Beauty’ by Olaffur Eliassen

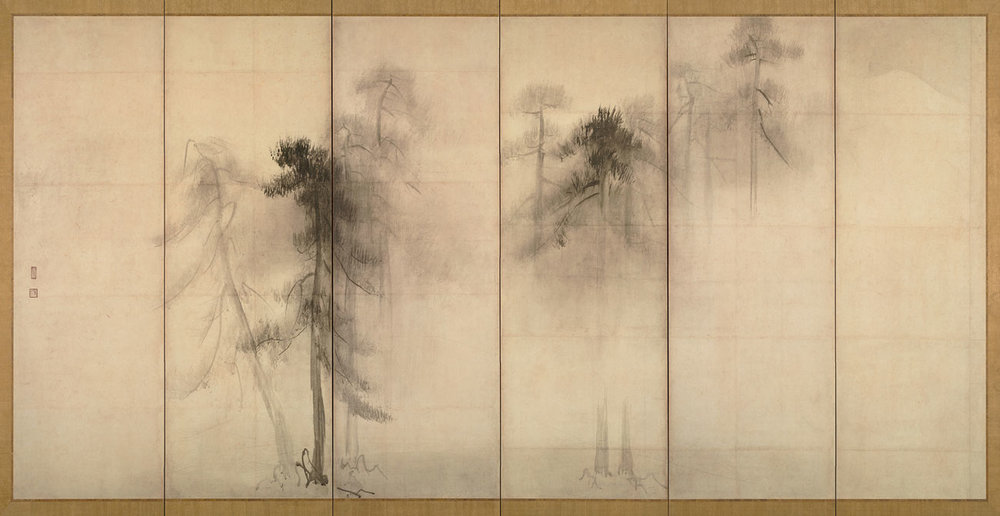

‘Pine Trees’ by Hasegawa Tōhaku

Eden Lonsdale

Photo by Anton Lukoszevieze

Autumn Willow by Hasegawa Tōhaku