Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at234 G O M B E R T

Nicolas Gombert & James Weeks

Seven motets and a chanson by Renaissance composer Nicolas Gombert (c.1495-c.1560),

arranged for instruments and with interludes composed by James Weeks.

1 Prelude

2 Nicolas Gombert Mille regretz youtube extract 1

3 Nicolas Gombert In te, domine, speravi

4 James Weeks media vita i

5 Nicolas Gombert Super flumina Babylonis

6 Nicolas Gombert Musae Jovis youtube extract 2

7 James Weeks media vita ii

8 Nicolas Gombert O rex gloriae

9 Nicolas Gombert Media Vita

10 James Weeks media vita iii youtube extract 3

11 Nicolas Gombert Tribulatione et angustia

12 James Weeks media vita iv

13 Nicolas Gombert Lugebat David Absalom

Discussion between composer James Weeks & producer Simon Reynell

James Weeks: As the Gombert project was your initiative, it’s probably best if we start by me asking you some questions, and then we can reverse roles later. So, first of all, why did you want to initiate this project?

Simon Reynell: I’ve been a fan of early music for a long time, but – although there have been some hints of this in Another Timbre’s output – it’s not something that the label has confronted head on. However, the amount of time I spend listening to early music has increased from about 10% of my leisure listening around the time that I started Another Timbre to about 50% today. What actually prompted me to take the plunge and release some music from 500 years ago was being diagnosed with cancer last year. I knew that the cancer was likely to be treatable, but I also knew there was a possibility that it wouldn’t be, and during my long wait for surgery I inevitably had some end-of-life-type thoughts – such as ‘are there any things that I’d like to do but haven’t yet done?’ With regard to music the main thought along these lines was that it would be interesting to see what happened if I took some of the early music I love and asked Apartment House to record it: how might it be different from existing realisations by early music groups? Would they find something new in the music? I realised quickly that any such project would need the help of a composer who was familiar with both experimental and early music, and that’s why I approached you.

JW: That’s really interesting. You and I certainly do share that passion for both early and contemporary music – and I too spend half of my listening time with early music. I’d guess that more widely there’s a significant overlap between people who listen to contemporary music and early music because there are so many ways in which the two speak to each other across what happened in between. But why were you interested in Gombert in particular?

SR: The quick answer is that he’s my favourite early music composer! But it’s not just Gombert; it’s the generation of composers of which he was a part that particularly interest me. Renaissance polyphony began in the fifteenth century, reaching a highpoint around the turn of the century when a generation of really gifted composers – the most famous being Josquin Desprez – developed a more complex, imitative counterpoint. I love the music of Josquin’s generation, but Gombert belongs to the generation that followed his; various composers who tried to extend Josquin’s innovations even further and push things to the limit, so that the polyphonic weave becomes really dense and complex.

So, if you take a piece like Mille regretz, which is the first piece by Gombert on the CD, Josquin had composed a beautiful and very famous version of this chanson for four voices. Gombert then wrote a new version, and, typically, added two more voices, so it becomes a 6-part song with more complex polyphony. And, equally typically, the two voices he adds are low voices – a tenor and a bass – which gives the piece a darker colour than Josquin’s, though I think both are equally beautiful. I think it’s that complex polyphonic web that I really love in Gombert, combined with the fact that in spite of the complexity, he is nonetheless able to weave in really engaging melodies, perhaps more successfully than other composers of his generation.

JW: Yes, I can see that, and I think Josquin had a similar sort of ability with melody. But that generation between Josquin on the one hand and then some other big names who come later – Lassus, Palestrina, Byrd and so on – has been referred to as the lost generation. As you say, they complexify what Josquin was doing and create music with these really rich textures. But then I suppose I’d ask – rather provocatively – how come a label that is renowned for championing reductionism is now championing the most intricate and sumptuous polyphony?

SR: That’s a good question, but I think there has been a gradual shift in the label’s output since, say, 10 years ago when I released the Wandelweiser box set - away from the most reductionist music towards slightly denser and more complex formations. So, for instance, while in the past a lot of the label’s output was duos and trios, more recently I’ve released quite a lot of pieces for larger ensembles – quintets, sextets, octets – so I must be craving something richer and denser. But it’s a matter of degree; I still love a lot of reductionist music when it’s well done.

JW: I feel similarly as if I’m moving between those two inclinations as a composer. Sometimes I feel a real need to pare down - almost to an unbearable degree, but then sometimes I want that absolute sumptuousness of texture and of things piling up on top of each other.

But when we first talked about this project it was clear to me that you had very strong aesthetic preferences about how Gombert’s pieces should be performed – and we had quite a bit of to and fro about which recordings you liked best and so on. And then of course you wanted them to be performed on instruments rather than using voices – which is actually entirely typical of the sixteenth century in that instruments and voices seem to have been pretty interchangeable. In church you’d get voices, but all these pieces had other lives outside and you could, for instance, double the vocal part with an instrument ad lib, and people were making instrumental versions of this music throughout the sixteenth century. But could you say what it is that you wanted to hear in Gombert’s music?

SR: Obviously a lot of Gombert’s music – and Renaissance music generally – was religious and was composed to be performed as part of a church service. But, as you say, even in the sixteenth century much of it also acquired a life outside the church, and I suppose I wanted to push this further and see what happened if you pulled it as far away from the church as possible. So yes, using instruments rather than voices was part of this, but I also wanted to react against what I feel is a rather pious, precious quality to the way early music is still often performed today. There are lots of exceptions to this and many people in the early music world are doing excellent work, but it’s still common to record and perform the music in churches with a heavy reverberant acoustic (which I don’t like), and for it be sung with a kind of angelic quality to the voices, as though the music is completely removed from the strife of the world, and is a sublime moment of contemplation aside from the messiness and dirt of everyday life, work, politics and so on. I think that is such a misreading of where the music actually comes from - and Gombert is a particularly clear example of this because he was directly employed by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, who was a music lover, but was also a very militaristic and brutal ruler. Charles V was using the wealth plundered from his empire’s new colonies in the Americas to fund multiple wars within Europe in an attempt to expand his already extensive territories there, and these wars were often fought in the most brutal ways, not dissimilar to Gaza today, with long sieges, massacres of civilians, starvation being used as a weapon, and so on. And Gombert was right there beside Charles V as he was doing this. Gombert was in charge of the choir at the court chapel, which was based in Spain, but they travelled with Charles either to various ceremonial events taking place in different corners of his empire, or sometimes even to the battlefields where one of Charles’s armies was fighting.

This is why I laugh when people say you should keep politics out of classical music, because it’s there right from the start, and for the next three centuries almost all major composers were employed or supported by dukes, counts, lords or kings who were all very much involved in the messy politics of the day. And in the sixteenth century the church was far from being removed from all this; this was the beginning of the Reformation, and Protestants were rebelling against the established church, sometimes violently, and the Catholic establishment – in which Charles V was a major player – was attempting to suppress it, again often in violent and brutal ways. So far from being a refuge or retreat from worldly affairs, the church was at the very centre of the power struggles of the day.

Obviously you don’t need to know that history to enjoy the music, but it does make me sceptical of any presentation of Gombert’s music as being sublime, pious or otherworldly. So I think in this project I wanted as much as possible to expel the angels from Gombert’s music, and present something which, yes, is extremely beautiful, but also has a slightly rough, everyday quality more akin to the actual circumstances of its original production.

JW: I agree with you. I think some sections of the British – and indeed the continental – choral scene have a tendency to package Renaissance music as a kind of chill-out scene. And this has been going on for decades, I think ever since people realised how beautifully they could sing it. If you listen to choirs in the 1950’s and 60’s trying to sing Tallis or whatever, they struggled with it and it isn’t very beautiful, because singers trained in bel canto don’t produce the right sort of sound for complex polyphony. And it isn’t till the late 70’s that you get groups like the Tallis Scholars who developed this beautiful, angelic style of singing. As someone who has half a foot in early music vocal ensemble practice, these debates continue and there are all sorts of different takes on it. An ensemble like Graindelavoix have a very different way of interpreting it that definitely isn’t holy or removed.

SR: Yes, at their best they are one of my favourite ensembles.

JW: Absolutely, but you shouldn’t mistake it for being authentic or historically accurate – they’re playing as fast and loose as they want, and why not? In fact I love that these pieces always have to be re-interpreted because we don’t know exactly what they sounded like or exactly how they were performed in the sixteenth century.

Another thing that struck me when we were preparing for the recording was your insistence that you didn’t want the music to have dramatic expression pasted on in performance.

SR: Yes definitely, and that was partly why I wanted Apartment House to play it, because they don’t do that; they don’t use vibrato, or slightly slow the tempo at points of potential pathos, or add little crescendi or diminuendi to emphasise emotionality. I wanted them to play Gombert in the same way as they’d play a piece by Laurence Crane, simply presenting the music as it’s written in the score. But that leads to something I was going to ask you, because obviously in Gombert’s day composers didn’t add dynamic marks to the music: piano, forte etc. That would all have been worked out by the singers in practice, and I imagine that Gombert, who was a singer himself, may have proposed plenty of dynamic shifts and phrasings with his choir. But when you prepared the scores of the motets for recording, you didn’t write in dynamics; we simply gave the musicians a general instruction that they should play roughly mezzopiano, with the highest voice hovering slightly above the rest at mezzoforte.

JW: Yes, that was partly because you sent me an email saying I shouldn’t write out dynamics!

SR: Ah, I’d forgotten that….

JW: But I wouldn’t have anyway because if I were working with EXAUDI, my vocal ensemble, on a piece by Gombert, I wouldn’t mark it up with lots of dynamics because first of all in rehearsal you look at the text and what the rhetorical highpoints are, and then when you start singing it you begin to realise how it’s shaped, and it sort of naturally has some rises and falls, and good singers or players will be recognise that. And on this project when we were discussing the instrumentation I think we sort of took that into account. We decided very quickly that we wanted a varied ensemble, not just strings, but mixing strings and woodwind, and we both agreed that clarinets should be central…

SR: …even though they’re an anachronism.

JW: Yes, we should be clear from the start that authenticity in terms of timbre was not on our menu here; we were looking for another timbre.

We also chose low flutes, which could have been hard to integrate, but when I listen to what Kathryn Williams was doing, I think it adds something really lovely, and for me it associates with the flute-like sound of a portative organ or something like that. An instrument that you wanted to add in, and which I didn’t have much experience of working with in this context, was the trumpet. I was worried that it might stand out too much, but you’ve worked with trumpeters using various mutes in very pared back contemporary pieces, and you’ve taught me something there because as soon as the trumpet came in it was clear how well it was integrated. Looking for precedents in Renaissance music, there’s the cornett, which isn’t a straight-up brass instrument, but has a tone that is similar to the muted trumpet, and I think it worked beautifully.

Then it was just a matter of trying to ring the changes and bring in enough variety by responding to the specificities of each piece, working out which instrument should have the melody line and so on. In retrospect I expended too much angst on that, as the beauty of Gombert’s music is that you could almost choose the instrumentation blind because it all works and you’d just have different colours coming out. I suppose the other principle was that, going up the parts from bottom to top, we’d alternate wind and string parts, so that you wouldn’t get blocks of similar timbres in one register or another.

I think that the results are fascinating, and that we did manage to take it well away from the church or holiness, so that a piece like, for instance, Musae Jovis, has a wonderful gritty, grungy sound because we put the bass clarinet right at the bottom. I’ve really enjoyed discovering the insides of Gombert, of how the melodies are shaped, and preparing the individual parts I could get a real sense of how he thought as a composer. Also, because all the parts are clearly defined timbrally, you hear things that you probably wouldn’t hear in a beautifully homogenised choral version. Is that what you feel too…?

SR: Yes, I do, but at the moment I still feel too close to the recordings to be able to really judge them. I’ve played them virtually every day for the last two months, and I still keep making tiny tweaks to the relative levels of one or other instrument; it’s kind of obsessive. But as a producer I do worry that this disc is going to appeal to a very small number of people. As you said, there is a crossover between contemporary and early music audiences, but we’re talking a niche within a niche. And I do worry that many of those on the early music side of the potential audience may not like the unadorned matter-of-factness of the realisations, and may not be happy that we didn’t try to make it sound numinous or ethereal.

JW: I don’t know, the first time I listened to it I turned up the volume and I was thrilled by the feel of spontaneous music-making that was going on. The Apartment House musicians are so good in that kind of context, and I think that if we’d spent a long time working on each piece in incredible detail, then you might get a more finessed performance, but you wouldn’t hear the moving parts of the composition so clearly. There’s a freshness to it, and in, say, Lugebat David Absalom, the big eight-part piece, which is more rhetorical and has these homophonic bits, and antiphony where the musicians are batting these little phrases back and forth, you can hear the musicians really leaning into that and there’s nothing precious about it, it just has a spontaneous energy and enthusiasm. An analogy might be a table that’s been sanded down, where you can see the materiality of it a bit more clearly.

SR: That’s a good metaphor. The one I had in my head when I was editing was a tapestry, and I wanted to be able to see every thread in it, and not have the upper voice dominate too much. And I think having instruments rather than voices really does help you hear each part more clearly.

JW: That interplay of timbres is anachronistic in that it’s probably not what instrumental versions in the sixteenth century would have gone for; they’re more likely to have arranged them for all viols or all wind instruments. But I’m not worried about what early music enthusiasts might make of the Gombert arrangements. They’re an unusual hybrid that have elements that are more typical of contemporary music than Renaissance music, so there’s always likely to be something that confuses or dismays early music people about what’s going on. If it reminds me of anything, it’s recordings of early music instruments from the 1960’s and 70’s. If you listen to those recordings they’re playing on not-yet-perfected copies of Renaissance instruments, using techniques that have also not yet been perfected, but the vitality and sense of exploration and discovery, of interrogating what is almost a foreign object, is definitely there and makes them still worth listening to. This is different because Apartment House definitely do have complete mastery of their instruments, but I think they were exploring and interrogating Gombert’s music in a similar way, and that gives the same kind of vitality, which is something you could definitely feel in the room on the day of the recording.

SR: I agree; I was really pleased with the enthusiasm that the Apartment House musicians showed because I hadn’t been sure what some of them would make of playing music that is 500 years old.

But let’s move on to the pieces on the album that you composed, which are kind of interludes between the Gombert pieces. When I asked you to write them, how did you decide what exactly to do?

JW: Well, you’d partly set this out when we first discussed the project. You said that you thought the Gombert pieces needed breaking up…

SR: Yes, because my experience of listening to a lot of Gombert CDs is that, however beautiful the music, after about 40 minutes your ears are really tired because the music is so dense, and you’ve been trying to follow all these different voices, and you just really need a rest or break.

JW: They certainly weren’t designed to be listened to in sequence in that kind of way. It’s the same with fifteenth century masses, where in the church service the polyphonic sections would have been interspersed with speech or monophonic chanting. So if, like on a Tallis Scholars CD, all the polyphonic sections are brought together, they can go on for 45 or 50 minutes, and be really beautiful, but it’s indigestible; you just can’t listen to them all in sequence. So I agree, and you gave me some pretty specific pointers; you said that you wanted some moments of stillness in amongst the constant flow of the polyphonic weave. And it became clear to me that we needed to change the timbre a bit for these resting points as well – to lose some instruments but maybe gain some others. And I very quickly thought let’s bring in a piano, partly because when I listen to music I often use the piano to pick out moments that seem to burrow more deeply into my consciousness. If I’m listening to a piece of Renaissance music there are often moments that I become obsessed by – conjunctions of lines into a cadence, or a passing chord in which a particular harmony is just touched but then the music moves on again.

And then I thought that for those moments of stillness it would be really interesting to create a kind of coloured silence – and that’s where the idea of soft sine tones comes in. Partly because I wanted to sort of de-nature the instruments a bit, and put them in a different world as quickly as possible. Then, when choosing the other instruments, we’d been talking about how the polyphonic weave in Gombert is quite dark, favouring lower registers, so out went the violin, but I kept viola and cello, together with clarinet and bass clarinet, to keep that balance of string and wind instruments from the motets.

Then, when I started taking on the idea of somehow breaking up the Gombert pieces, it happened to be very warm, and I was sitting in our music room at home with the sun pouring in, and I was thinking about Gombert in Spain. I had this image of his music as a set of tapestries hanging on all four walls, and what could I put between them? First I thought of a window, but that evolved into the idea of screens separating them – specifically those translucent Japanese screens through which some light passes, but also shadows and the outlines of the things beyond. So, as you know, my title for the first draft of these pieces was ‘Gombert Screens’, and in different ways I was thinking about how to create a kind of aural screen. In the first piece there’s this constant texture coming in and out underneath an oscillating piano chord, like shadows on a screen, and I was thinking of this almost claustrophobic warmth, and Gombert in Spain surrounded by fabrics and tapestries and the dark sumptuousness of his own music.

SR: So do the pieces pick up on particular pitches or chords from the surrounding pieces by Gombert?

JW: They do, but I was trying to make them strange so that they don’t quite sound like Gombert, so there’s quite a lot of microtonal adjustment of that modal world. The final pieces are quite modal, and when we were recording them people were reading expression into them. Someone said how sad one of them was, which I wasn’t particularly thinking, but that will happen if you use modal material as there’s a rich vocabulary of expression attached to it.

But also I was extracting those fragments of melody that I’d become obsessed with – like ear worms almost – and I was reducing and reducing them, and then trying to find ways to voice them, to give them new timbral life. So by the end they’d gone quite a long way from Gombert, but at the same time I hope people will think ‘oh yes, I can see how that probably came from Gombert’. And I was thinking of the sequence of the Gombert pieces as well, and whether we were coming after a piece with a relatively high register or not, or if we’d just had a particularly sad or lugubrious one, and so on.

SR: I have to say, I was very pleased with them. I think they work really well and slot in unobtrusively even though stylistically they’re obviously very different. But I think they do have an expressiveness, a melancholia about them, which Gombert’s music does as well – in fact 90% of the music I like is suffused with melancholia!

JW: Me too; I think we’re at one on that. But as you know, I eventually called them ‘media vita’, which is also the title of what is probably Gombert’s ‘iconic track’, if we can use that phrase! The full quote is ‘media vita in morte sumus’, which means ‘in the midst of life we are in death’, but I wasn’t actually thinking that far. I was thinking of moments that occur in the middle of life, like moments of stillness amidst the liveliness of the flow of Gombert’s pieces, which is what you’d asked me to create. But also, without wanting to get too heavy, moments of contemplation in the midst of life, like the one you referred to earlier when you were confronting having cancer. But then I think these moments when you reflect on life don’t have to be melancholic, and when I was writing these pieces I wasn’t sad, in fact I was thoroughly enjoying myself, so part of it was wanting to reclaim or re-capture the phrase ‘media vita’, and take it down a wholly different route.

SR: I think they work beautifully.

JW: I don’t know if other composers are the same, but when I finish something I always have l’esprit de l’escalier - you know, the feeling as soon as you’ve written the last note that there were two or three other things that you could have done instead and which might have worked better. But then when you have a fairly specific request like this, in the end you’ve got to go with what feels most essential for you, and maybe the other ideas will be the basis for the next piece. Because I think that is how things often do work going from project to project; you think well I tried that, but I could have tried this, so perhaps I’ll use this in the next piece.

SR: Great. Can we circle back now to Gombert, and one issue that we probably have to address is should people be playing his music? Because, as you know, at the height of his career working for Charles V, just as his reputation was growing and several volumes of his motets had been published, and some people now regarded him as the leading composer of the time, he was suddenly condemned to the galleys in disgrace for raping a choirboy. As I say, some people might argue that because of this you shouldn’t be promoting his music. Do you have any thoughts about this?

JW: It’s a difficult one. There is only one source for this, so we don’t know the details, but we have to assume that it’s broadly correct. So do we want to play music by people who have done awful things? It’s a good question. In this case obviously no-one involved survives, and 500 years on I think we have to present it with perspective, saying that this music exists, and is extremely beautiful, and it was written by someone who did something terrible. We’re not trying to hide or deny that, but it’s so far back in time that I myself don’t have an issue in performing it nonetheless.

SR: I think pretty much the same. Gombert was rightly punished in his time, and suffered badly because of it, losing both a very privileged post and his reputation, and being incarcerated with hard labour, so that even after he was pardoned by Charles V seven or eight years on, he never regained his position or standing as a leading composer, and he drifted into obscurity. To me that seems enough punishment, and I don’t feel that 500 years later we need to extend it further by refusing to play his music.

As a footnote it’s worth mentioning another very good composer of the same generation as Gombert, Dominique Phinot, who – according to Girolamo Cardano, the same source who tells us about Gombert’s conviction - was found guilty of “copulation with boys”. But Phinot was beheaded and burned for his sins, so in a sense Gombert got off lightly, probably because he was to some extent protected by Charles V. In some circles Phinot is now celebrated as an artist executed because of his homosexuality, and is remembered as a victim rather than a perpetrator, which I think is a bit difficult.

But it’s complicated, and I can’t help coming back to the general background of sixteenth century Europe, which I think we just have to acknowledge was an incredibly brutal place. And quite aside from the rape, Gombert is right there in the middle of it all, as I said before, implicated by close association with a man whose constant wars were causing huge amounts of death and suffering. And yet ironically Charles V was a great patron of music – not just for Gombert, but for several other composers too. Going back to Mille regretz, the Spanish title for that song is La Canción del Emperador – The Emperor’s song – because it was Charles V’s favourite piece of music, and he may well have asked Gombert to compose the new version which opens the CD. So, then as now, an involvement with beautiful music doesn’t inoculate you from the bleakest aspects of society. Our own governments seem to be leading the world into another brutal period of history, and I think it’ll be hard for any of us to remain completely free from any moral stain.

James Weeks

Apartment House

Heather Roche, clarinet & bass clarinet

Vicky Wright, clarinet & bass clarinet

Raymond Brien, clarinet

Rebecca Toal, trumpet

Kathryn Williams, alto & bass flutes

Bridget Carey, viola

Chihiro Ono, viola

Rachel Stott, viola

Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

Mira Benjamin, violin

Kerry Yong, piano

James Weeks, conductor

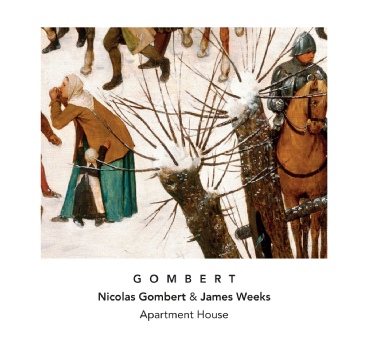

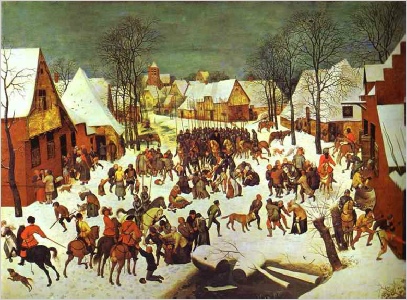

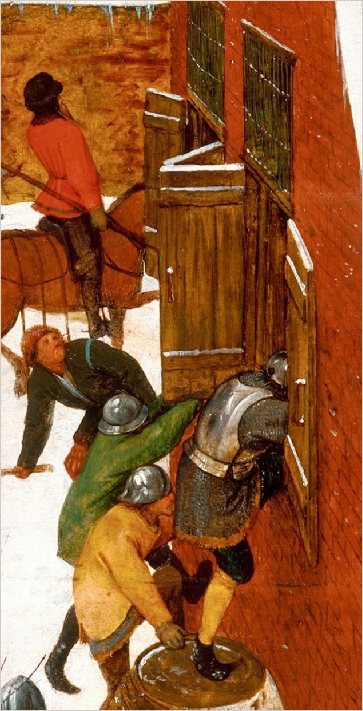

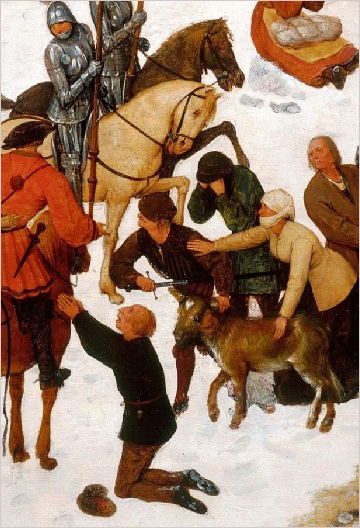

‘The Massacre of the Innocents’ by Pieter Breughel (1566)

(details below)

Other CDs by James Weeks

As well as the discussion below, you can also read Clive Bell’s great feature article about thie GOMBERT disc here