Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

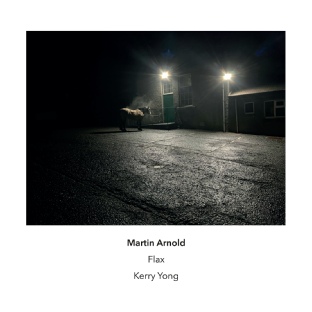

at221 Martin Arnold ‘Flax’

Kerry Yong, piano

An extended piano solo by Canadian composer Martin Arnold, dedicated to Philip Thomas, the outstanding pianist who commissioned the piece, but shortly afterwards became seriously ill. With Philip’s blessing, the project was handed on to Kerry Yong, who played it for this recording on the piano at St Paul’s Hall in Huddersfield which Philip used to frequently perform and record on.

Equally strange and beautiful music

Interview with Martin Arnold

Can you tell us how this project came about?

I feel like the beginning of this story is as much yours to tell as mine. On January 3, 2020, I received an email from our friend and colleague, the wonderful musician Philip Thomas, asking me if I would like Another Timbre to commission me to write a CD-length piano piece for him. I think you were reinvesting money made from Philip's astounding boxset of Morton Feldman's piano music. Of course, I was over the moon. My first thought was that I wanted to write a piece that really would fill up a CD, something around 78 minutes. Given that, I knew I wanted to make a piece that had a kind of obsessive but relaxed focus, that would involve material and ways of playing that wouldn't vary much. I really think for the kind of music I can offer, the longer the duration, the less the texture should change. The texture can be thick or thin or you name it, but there shouldn't be even a hint of epic narrative (therefore, little formal change and certainly no dramatic juxtapositions).

Then I remembered discussions I had with Philip about my music; in particular, I remember him saying something along the lines that I made him rethink the top register of the piano. So I decided I would write something where the right hand would stay in the upper range of the instrument for a really long time. That reminded me of my love for the recordings jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal made with his trio in the late 1950s, especially ones from the Pershing Lounge in Chicago in 1958. He improvises a lot of spare, spacious melodic lines, yet still with a polyvalent chromatic invention out of bebop (certainly Thelonious Monk did this as well, but Jamal's inventions are more demure, less overtly strange, though still very subtly mind-bending). But he keeps a lot of these melodies in the top two octaves of the piano; he doesn't use that register for embellishment, as a change of colour, he stays up there as if that's where a piano normally sounds. Thinking about Jamal, thinking about jazz, was the spark that got me thinking more specifically about this piece. Pretty much all of my music embraces some kind of continuous melody - and I could think of no good reason this should change with this piece - but I decided to engage more fully a kind of melodic invention that, while always influential to me, had only obviously surfaced a couple of times in my music previously. I love a lot of jazz, but I'm particularly enthralled with innovators of the 1950s and early 60s, who, while still playing over chord changes, carrying on from bebop, improvised lines that had only a viscously oblique relationship to the harmonies (I'm thinking about Monk, Herbie Nichols, Elmo Hope, Lennie Tristano, Paul Bley, Andrew Hill, Dick Twardzik, Misha Mengelberg... just to name a few pianists; and some pianists who came later: Connie Crothers, Geri Allen, Pandelis Karayorgis, Tania Gill...). Listening to that music, when they're playing lines, I want those lines to continue indefinitely. And, when they're bopping, I wonder what those lines would sound like slower, much slower.

In part, Flax addresses these desires: over half of the piece plays with that sweet-and-sour polytonality before it slowly morphs into the kind of modality and organum-like texture that my music more commonly explores. Flax never swings (I don't know if it even sounds anything like jazz; it's certainly not trying to); it's a slow-motion swaying, staggering unfurling of lines of pitches. I guess one other related feature that distinguishes Flax is that over half of it has a reoccurring set of chord changes; it's not a contrafact, the changes don't come from any standard I know, but they do emulate that harmonic world, along with the substitutions jazz musicians add to standards. While I was working on the piece, on December 12, 2020, composer-performer "Blue" Gene Tyranny passed away. I was really saddened by this; I'm a fan! I got thinking about how close his music could be to lounge jazz while still being utterly, singularly psychedelic. Thinking about that gave me the permission, the nerve, to use a pretty standard chord progression without much extra textural adornment.

How much did you take account of Philip's playing when you were composing the piece, and did you revise it at all when it became clear that it'd be Kerry rather than Philip who was going to perform it?

Since we started collaborating, Philip has mentioned that I write the kind of music he really knows how to play, that he relates to deeply in connection to how he sounds the piano (the first piece he played by me was in 2009; the first piece I wrote for him was in 2012). That's how it sounds to me when he's playing, and I'm so grateful for this! I've written a lot of upper register melodies for him over the years so I could profoundly imagine him playing Flax as it unfurled (I believe and will continue to believe that one day I will actually hear this!). I also knew he would whole-heartedly embrace the peculiar challenges of the piece (the duration and how that duration is articulated). When it became clear that Philip would be unable to perform the piece in the foreseeable future, I wanted someone I knew personally in Britain to play it. I had the pleasure of working with Kerry in 2016 when he played reed organ in my piece Stain Ballad as a member of Apartment House (Philip played the piano part). It was evident that Kerry was a fantastic musician; it was also great to work with him and to hang out and talk music with him. As much as anything, it was those conversations that convinced me he had the breadth of musical experience and perspective to engage and embrace Flax and all its idiosyncrasies. I was right (gratefully so)! No revision required!

Why the title Flax?

I was thinking about melodic lines and I love etymologies; "line: Old English līne ‘rope, series’, probably of Germanic origin, from Latin linea (fibra) ‘FLAX (fiber)', from Latin linum ‘FLAX’, reinforced in Middle English by Old French ligne, based on Latin linea." [the caps are mine] It's also a tasty grain and a great sounding word and linen is made from it!

I find Flax really hypnotic; it circles around its own dreamy soundworld according to rules that remain opaque. Is that sense of creating a unique soundspace something you consciously attempt when composing?

I think trying to imagine a soundworld I wanted to hear, that was different than other ones I was already able to visit, used to be more of a conscious desire, a creative impetus for me (I just wanted it to be different; it didn't have to be unique in any exemplary way). But that has receded as something conscious; now, the soundworld emerges from, is constituted by, more specific material, contextual speculations that are banging around in head while composing the piece. However, I continue to want my music to encourage the listener to feel that they're on on a trip, paying close attention to their lifeworld, exploring details in a space their imagination is moving through, rather than feeling they need to understand a message that's being delivered to them. With Flax, having adopted some initial propositions about texture, I was really just fixated on pitch and rhythm. And pitches in rhythms can make weird, subversive magic, can be dream-works (yep, I'm thinking about Freud here) that give rise to intense, obsessive dreams (keeping in mind that "hypnosis" comes from Greek hupnos ‘sleep’).

You don't seem to write many short pieces (ie less than 20 minutes), and I wondered why? And at a very long CD length (79 minutes) is Flax the longest piece you've written to date?

Well, I do have some shorter pieces: Stain Ballad is 13 minutes long, Slip is 15, Lutra is 17; there are a few more pieces 15 minutes or less on my Soundcloud (although, none of them have any drama, any narrative tension, so for some, everything I write is too long). Flax is my longest continuous composition. However, the two movements of Burrow Out; Burrow In; Burrow Music add up to an hour and 51 minutes; one can listen to my sound installation Fancy for as long as it keeps playing wherever it's installed, without it ever repeating; and I recently collaborated with Scott Thomson on Enamel, an open-ended piece for solo trombone - 5 hours of it just was released by the label Rat-drifting on Bandcamp (I really thank Scott for that! I listened to him play Enamel for 3 and 3/4 hours, live in Montréal! - that's right: solo trombone!). I think about, care about the duration of my music a lot, but it's always arrived at in relation to the context in which it is being written for, usually (to different degrees) in conversation with whoever has asked me to write the piece (I don't produce music unless I'm asked). Flax is 79 minutes long because Philip wondered if I was interested in writing a CD length piece.

Martin Arnold