Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at157 Giuliano d’Angiolini ‘Antifona’

1 - ‘Ad ora incerta’ for orchestra (2018) 10:14 Youtube extract

Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, cond. Tonino Battista

Live recording from the AngelicA Festival 2018, with thanks to AngelicA

2 - ‘Aria1’ for piano (2016) 10:11

Giuliano d’Angiolini (piano)

3 - ‘Antifona’ for flute & piano (2018) 11:31

Manuel Zurria (flute) Mark Knoop (piano)

4 - ‘Litania’ for six instruments (2017) 15:04 Youtube extract

Apartment House

CD copies sold out, but downloads still available from Bandcamp here

Interview with Giuliano d’Angiolini

On the cover of your CD you say that the compositions "follow strict procedures of indeterminacy (realised by diverse techniques). Each performance sounds different, with pitches, durations, harmonies and instrumental combinations changing". Can you explain how this indeterminate element works in each piece?

In the orchestral part of Ad ora incerta long sustained tones and fragments of melodies are placed into time zones, which are measured in seconds, but whose boundaries fluctuate : it’s Cage’s system of ‘time brackets’. The precise order of events is unpredictable as well as their combinations, but the composition is conceived in such a way that – whatever happens – the basic harmony is always consonant. However, the piano part is fixed and entirely written out, in contrast with the orchestral parts on which it is superimposed.

In Aria1 the pianist has a group of between three to five notes available for each attack. The notes are all from a pentatonic scale which slides progressively across the chromatic field. No duration is specified, which obliges the interpreter to become involved to some extent in the compositional process.

Litania applies the same principle to an instrumental ensemble, but here there is a distinction between long and short notes (though exact durations aren’t specified). In addition the density of the music is variable because each player may start at whatever point they choose after the preceding musician has begun to play, but before this one has finished his sequence of notes.

These three works apply indetermination processes as much to the articulation of events in time as to the organisation of sounds.

In Antifona the score offers a choice between several different sounds for each attack, but the duration of each sound is precisely notated.

Indeterminacy can point in different directions. Some see aleatoricism as a kind of objective discipline and wouldn’t want any input from the performers, whereas others welcome musician choices as an interesting way of building in unpredictability. How do you see your music within that spectrum, and why do you continue to take the path you do ?

First it is necessary to distinguish between ‘randomness’ (alea), ‘chance’ and ‘indeterminacy’. These are different things. As to the role that the interpreter plays in my compositions, well, it’s variable. Often musicians have a lot more freedom than in music that is entirely determined, including the freedom of not being obliged to count beats or bars, which allows them to ‘live’ the sound and music in a more intimate way. Sometimes the musician can choose from a large range of actions, and so is given a more large degree of responsibility in the musical process, as happens in Aria1. This greater involvement of the interpreter brings with it a particular discipline. In the score I specify that « the choice of notes should not be made according to a logical system or a predetermined plan. The performer should remain serene and open both to choices which arise from personal taste and to what is unpredictable. If a figure appear, let it out, so that each event can truly be itself. »

In Aria1 (as well as in Cantilena, which featured on my previous Another Timbre CD) everything is reduced to a simple melody, stretched across time and centred on the sounds. Indeterminacy enables each performance to have the freshness and the element of surprise that you experience when you first hear a piece, before you can establish more precisely the relationships between events in the music, and before you can fix them within mental categories.

In all aspects of life our brains never stop to smooth discontinuites and imposing a direction to the events. Our brains are always establishing causal relationships between phenomena using both memory and anticipation. It’s a fundamental activity which makes our intelligence an instrument that is working for our survival. These attitudes makes that our brains are « starved of stories », as Oliver Sacks puts it.

A large part of musical art (as well as cinema or theatre) is spontaneously in phase with these thought mechanisms and corresponds to the habitual requirements of our mind. Now for me it’s a question of proposing a different experience, that of a music without development ; a music which privileges the precept rather than the concept, and which escapes the laws of cause and effect. This is the essence of art : it allows us to discover worlds which we don’t yet know.

Indeterminacy is a way of achieving all this, and that is why it continues to play a central role in my compositions. This isn’t a matter of an ideology that I impose to myself but is a profound necessity: I write the music that I need.

However, I don’t discount the possibility that a composition might be entirely determined, as long as it is done with an open spirit and the approach is non-intentional.

You describe Ad ora incerta as being for ‘orchestra’. How large was the ensemble in the recording, and how large could it be for that piece? Is your music better suited to small ensembles, both in terms of the delicate soundworld you prefer, and is it harder to produce satisfactory results with large ensembles using indeterminate systems ?

Ad ora incerta was composed for a small orchestra – in this case about 24 musicians. The number of strings may vary a little, but the size of the ensemble remains smaller than a full orchestra.

I find it easier to collaborate with specialist ensembles or soloists, who are more inclined to study the more delicate aspects of the music. Quite often my music is not based on those things which musicians spend many years studying and which they are used to mastering. Sometimes I ask them to use methods of playing, or to rethink their habitual gestures and techniques, in ways that run counter to what they have learned. For example, I ask violinists to hold a single note as long and as constantly as possible for the length of a whole bow. It should be an elementary gesture, and yet in practice trained violinists often find this difficult. Moreover, some systems for applying indeterminacy require unusual behaviours which can’t really be applied with a large ensemble.

An orchestra is a heavy and rigid organisation, closely bound to the repertoire for which it was created. It has not really evolved for a long time, either in terms of the instruments used, or in terms of acquiring new techniques or new ways of playing. In spite of a few episodes where it has opened to some extent to contemporary music, the orchestra generally lacks a dynamic which would allow it to become a living musical reality : it only exists for the ‘great repertoire’ of the past. Playing many of my scores demands a degree of engagement and mental openness which you can’t really ask of an orchestral musician in the current state of affairs. Having said that, I can adapt my composing to any ensemble, and if I haven’t worked more with orchestras, it’s also because orchestral commissions to contemporary composers are very rare, and I’ve given up in advance.

Finally I wonder how you think the C-19 crisis is affecting and will change both your own practice as a composer, and experimental music generally ?

In our regions the virus will disappear quickly; but this isn’t the case with the attitude of our governments, who invade our lives and want to control us. Disregarding commercial music, today we mostly play music from past centuries. But that has never been the case before: people have always been thirsty for the new; at the end of the Middle Ages people forgot the music that had been composed thirty years previously, and forgot the names of the composers of the generation that preceded it.

Following the pandemic, in France and Italy all artistic activity ceased. Ifear that it would have been like a life-size exercise in which there is no longer room for modern music - or experimental music, as you call it. I’m sorry to be so pessimistic, but the situation in these two countries has been catastrophic for many years (England seems to be different). Composers have a share of responsibility for this. A long time ago I wrote: “Music is everywhere. It satisfies certain functional necessities: it can serve as a support for dancing, it can liberate energies, or, on the contrary, it can offer a reassuring sense of order, a soothing aura. It can be decorative, a background, intended to create an atmosphere or fill in the pauses in conversations. It also fills spaces in restaurants, cafes, shops, supermarkets, airports, sometimes even the streets. We don’t listen to it…. I take account of this change in the ways that people hear music and I try to take advantage of it. The music I write can be listened to with concentration or with blissful indifference. Perhaps it has the merit of not imposing itself. It’s a music which presents particular events for one’s attention, but which doesn’t evolve, and which offers nothing in terms of form. It can remain in the background, like Satie’s ‘furniture music’, without anything being lost. Everyone is free to listen to it, or not listen.”

However, I fear that even this approach doesn’t meet the collective need, and lacks the necessary curiosity of the listening public. A curiosity which, I remember, fed the liveliness of the 1970’s and 1980’s.

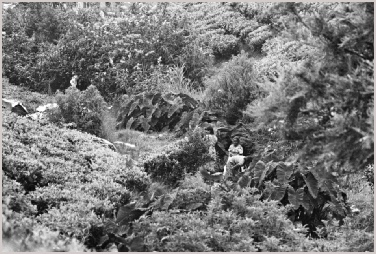

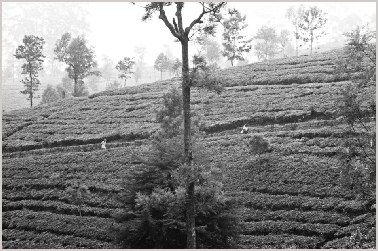

Photo Fiammetta d’Angiolini

Reviews

“At The Heart Of Sound With Giuliano d’Angiolini by Michele Tosi, ResMusica

Giuliano d’Angiolini, who has just turned 60 years old, composes low-energy music using indeterminate processes which he keeps secret. He is a creator for whom composition seems to be an initiatory journey: the four works brought together in this new album bear witness to this.

Except for the first piece, Ad ora incerta, whose title is borrowed from the writer Primo Levi, the titles of the other three works on the CD refer to the voice. D’Angiolini’s music sings, first through the piano, played by the composer himself, in Aria1, whose ‘lost song’ seems to abolish time. A slow immersion in the bass keys proceeds in stages articulated by silences. Each sound is heard in and for itself, the effect of the pedal resonating waves in an aquatic transparency and soft voluptuousness.

In Antifona flute and piano respond to each other according to a principle of alternation, where the interventions of the flute gradually become tighter. The wind instrument, played by the magnificent Manuel Zurria with a hugely sensual sound, weaves between breathiness and a colouring of sound, while the piano, bathed in resonance, makes one forget hammers striking strings, and generates acoustic illusions with beats and kinetic movement.

In Ad ora incerta space is opened out and temporality floats. d’Angiolini “lets the sounds be what they are”, thanks to the processes of indeterminacy, even if the piano takes a leading role, endowed with an attractive force which draws together this community of tones. The spectral canvas shifts towards the bass in a slow process: an immersive listening experience well conducted by Tonino Battista and the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

In Litania for six instruments (flute, trumpet, violin, cello, piano & marimba), the flagship work of this recording, colours are filtered through breath and muted strings but without becoming confused. Attacks are always individualised and textures developed. By playing with different features of sounds (vibrated, or not), its grain (more or less dark in the strings), and its duration, d’Angiolini creates a surprise (with the superb marimba) and magnifies the differences between sounds. Like Antifona, Litania abolishes time and makes us listen to sound in its d’Angiolinian jubilation.”

Photo Fiammetta d’Angiolini

Photo Fiammetta d’Angiolini